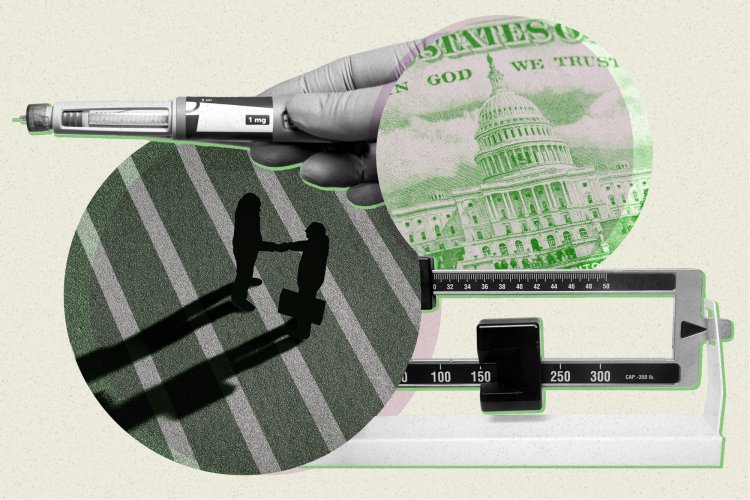

DC lobbying frenzy ignited by weight-loss craze

President Donald Trump faces mounting pressure regarding the accessibility of anti-obesity medications and the potential inclusion of these drugs in Medicare coverage.

The Trump administration is currently facing significant pressure regarding the accessibility of these medications and the potential for Medicare to provide coverage. Although the administration has thus far leaned against supporting the manufacturers of weight-loss drugs, the debate remains unresolved.

The political discourse surrounding anti-obesity medications has intensified in Washington, particularly following a prolonged supply shortage caused by unprecedented demand. From 2022 to 2024, the market was largely filled by cheaper generic versions, but as supplies returned to normal, brand-name companies are urging federal regulators to restrict the sale of these less expensive counterparts, referred to as compounded drugs.

In addition, the pharmaceutical sector is advocating for the repeal of a two-decade-old regulation that prohibits Medicare from covering weight-loss medications. Thus far, officials within the Trump administration have expressed concerns over costs as a reason for their opposition. However, supporters contend that the initial investment would be outweighed by long-term savings derived from fewer individuals suffering from obesity-related chronic conditions.

The high stakes of this situation have led to a surge in lobbying efforts.

In the first quarter of 2025, Novo Nordisk, the maker of Ozempic and Wegovy, spent in excess of $3 million on lobbying endeavors. Eli Lilly, which produces the weight-loss drug Zepbound as well as Mounjaro—a similar medication for diabetes—matched that spending. Together, these companies engaged over 10 lobbying firms, including prominent Washington players Avoq, Holland and Knight, and Williams and Jensen, as per a PMG analysis of lobbying records.

Hims, a notable telehealth provider offering a generic drug, also sought out lobbyists, and competitor Ivim Health has recruited Sean Spicer, previously the press secretary for the Trump administration, as a spokesperson for Washington. Both companies are involved in the distribution of weight-loss medications.

During a meeting in the Oval Office early in his new term, President Trump discussed obesity drugs with the CEOs of Eli Lilly, its competitor Pfizer, and representatives from PhRMA, according to a lobbyist who attended.

As lobbyists present their arguments to the Republican-led administration, they encounter two challenging factions—Republicans who are resistant to policies that elevate federal spending and proponents of Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s "Make America Healthy Again" initiative, who argue that reliance on Big Pharma undermines better dietary and lifestyle choices.

Pharmaceutical firms are adapting their messaging to address Kennedy’s apprehensions.

“While medicine isn’t always the answer, sometimes lifestyle and diet are not enough to prevent or treat chronic diseases like obesity,” stated Shawn O’Neail, a lobbyist for Eli Lilly. “That’s where medicine can make a positive difference as part of a well-rounded approach to chronic disease.”

In a polling effort conducted by the healthcare think tank KFF last year, it was found that 12 percent of American adults have utilized GLP-1s, the class of drugs under discussion. From November 2023 to October 2024, Medicare spent $14.4 billion on Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus, a GLP-1 pill, according to figures released by the agency in January. Medicare does provide coverage for these drugs when prescribed for non-obesity conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease.

According to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office, if Medicare were to cover these medications for obesity treatment, it could result in an expense of about $35 billion from 2026 to 2034. Though the exact numbers regarding compounded medications are unclear, industry executives estimate that millions have opted for these alternatives, similar to the brand-name disbursements.

The debate over access puts pharmaceutical giants such as Eli Lilly in conflict with telehealth platforms marketing cheaper generic drugs. Smaller companies and their advocates assert that patients still struggle to find brand-name products like Wegovy and Zepbound at their local pharmacies, despite the FDA’s assurance that the shortage has ended. Compounding pharmacies also argue that their versions offer greater availability at reduced prices, especially since insurance coverage for the branded medications is inconsistent.

The FDA had allowed compounding pharmacies to create copies of Wegovy and Zepbound during declared shortages by using ingredients from approved manufacturers. However, once the FDA declared that the shortage had ended, the production of these copycat drugs became prohibited, albeit with some time granted to phase out operations.

Both sides are seeking potential allies within the Trump administration.

The pricing of these drugs caught the president's attention. In a February Fox News interview, Trump expressed his dissatisfaction over the "very unfair" price disparities between European and American markets regarding the “so-called fat drug or fat shot.”

FDA Commissioner Marty Makary, a known critic of the U.S. healthcare system's costs, previously served as an advisor for Sesame, a telehealth platform offering compounded GLP-1s. Medicare chief Mehmet Oz has long advocated for the benefits of these drugs, and Trump advisor Elon Musk has acknowledged using them, advocating for lower costs for average Americans.

However, Kennedy remains a significant figure in the ongoing discussion. His views on GLP-1s—along with Big Pharma generally—suggest that he will be a tough opponent to sway. He has raised concerns that pharmaceutical companies are more interested in selling drugs to entrap consumers than in encouraging healthier choices through diet and exercise.

While Kennedy has moderated his stance on these drugs since his nomination, he has continued to express doubts about their long-term safety and affordability.

“There’s a lot of temperature checks still happening with how the Trump people and particularly … the more RFK wing of the administration feel about anti-obesity medications,” remarked a lobbyist working in this sphere.

Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies and telehealth platforms are aligning with advocates linked to Trump’s administration.

Greg D’Angelo, who led health policy efforts in the Office of Management and Budget during Trump’s initial term, has recently registered to lobby on behalf of Novo. The Danish pharmaceutical firm has also partnered with Checkmate Government Relations, a North Carolina lobbying group with strong connections to Trump’s circle.

Lilly similarly engaged Checkmate in January and has also brought on a Trump-aligned lobbying firm that includes Garrett Ventry, a former aide to the Senate Judiciary Committee and long-time adviser to influential Trump ally Rep. Elise Stefanik.

Certain lobbyists are attempting to persuade the administration that many of Trump’s rural voters could benefit from federal coverage for weight-loss drugs. A compelling argument is that providing such coverage could ultimately lower costs associated with treating related chronic diseases.

Earlier this month, the administration rejected a proposal from the Biden era that would have allowed Medicare to cover weight-loss medications by interpreting the law in a new way. However, the Medicare agency indicated that it might consider revisiting the coverage question based on an analysis of costs and benefits.

“We were disappointed with the decision on the [Medicare] rule, but we are hopeful that it’s more of a ‘not now’ than ‘not ever,’” commented O’Neail from Lilly.

On the telehealth front, Hims engaged Continental Strategy in January, paying the firm $90,000 during the first quarter to liaise with Congress and the administration. The Washington and Florida-based firm counts among its partners Katie Wiles, the daughter of White House chief of staff Susie Wiles. Hims disclosed lobbying expenditures of $440,000 for the last quarter.

Ivim Health, which is among a number of telehealth companies that emerged recently in response to the GLP-1 trend, has adopted a different strategy by recruiting a former patient who had previously worked for the president to advocate for patient concerns regarding upcoming deadlines that may compel online suppliers of cheaper drug alternatives to cease operations.

Spicer, who had acquired a six-month supply of a compounded version of Lilly's drug prior to Ivim Health halting sales, is promoting these products with a modern conservative viewpoint—emphasizing both long-term savings prospects and the genuine issues faced by consumers struggling to find the brand-name products at pharmacies.

“All I know as a lay person is, a shortage was declared of a drug that millions of people use,” Spicer told PMG. “If they can’t get it, by definition, the shortage still exists.”

Novo and Lilly are now emphasizing the availability of their medications after a prolonged shortage that left many patients scrambling for their prescriptions. They are focusing on the safety of their FDA-approved offerings compared to those produced by compounding pharmacies, which do not have to adhere to the same regulations, while acknowledging Kennedy’s focus on addressing the “chronic disease epidemic.”

“Our health is built on a good diet, on exercise, on sleep and smart lifestyle choices,” Lilly CEO Dave Ricks stated in February during a Washington event promoting the company's domestic manufacturing initiatives. “But we must admit that sometimes that’s not enough to prevent chronic disease, and when it’s not, we need medicines to manage those diseases effectively.”

Ricks, one of the first pharmaceutical executives to engage with Trump after the 2024 election, has highlighted Lilly's status as a U.S.-based firm to resonate with the president’s “America first” agenda while opposing Trump's proposed tariffs on medications.

Both companies have initiated legal actions against providers of generic products that they claim have been falsely marketed as safe and effective, a distinction that implies FDA approval—something compounding pharmacies do not undergo.

Contrarily, telehealth providers and their pharmacies assert that the drug manufacturers' criticisms have unfairly conflated their offerings with counterfeit medications that may pose severe risks to patients. Ivim Health has expressed concerns in legal documents that eliminating its compounded drugs without guaranteeing access to branded products would push patients toward potentially dangerous or fraudulent alternatives available online.

Currently, it remains uncertain where the Trump administration will ultimately land on this issue. While Kennedy expresses skepticism regarding weight-loss drugs, many lobbyists assert that a significant portion of the American public seeks enhanced access to these medications.

Anti-obesity drugs “are everywhere,” one lobbyist asserted, “and the more we can make that a personal issue for policymakers, the more they’re generally sympathetic to coverage and other related matters.”

Sophie Wagner for TROIB News